Excerpt Interim Letter 2023

- Oct 6, 2023

- 8 min read

Updated: Apr 5, 2024

Portfolio Management

I believe my investing approach differs significantly from the mainstream, where most investors’ decisions are largely emotional and influenced by the apparent signaling value of price fluctuations. Instead, I look to the teachings of Graham, Buffett, Munger and their cohorts. To me, intelligent investing revolves around making a few well-informed decisions based on factors within my control when I believe the odds are stacked in my favor, and I size my positions according to the level of comfort and potential outcomes. While winning every time may not be feasible, consistently making sound decisions likely leads to enduring success.

My decision-making criteria focus mainly on the disparity between a company's intrinsic value (determined by its future cash flows) and its market price. The larger the discount to my estimate of intrinsic value, the safer the investment and the greater the likelihood of substantial gains. My quest for mispriced odds thus hinges on a probabilistic mindset.

Once I've evaluated an investment opportunity, the focus shifts to sizing the positions accordingly. In practical terms, this means adjusting the size of an investment based on the probabilities of success and failure, as well as the potential returns and losses associated with each investment. I'd rather acquire shares in a company trading at 2x earnings power, which roughly equates to a 50% earnings yield, than one trading at 10x earnings power, offering a 10% yield. However, a low multiple doesn’t do the trick alone. My assessment is also based on the stability of a company’s cash flow, as well as my visibility into a company’s future.

Over the past few months, as some of iolite’s holdings faced significant declines due to irrational market selling, I increased iolite’s exposure to these situations. In the short term, this move hurt performance, as the stocks I sold (more liquid, higher multiple, in-favor companies) continued to rise while those I bought (less liquid, lower multiple, out-of-favor companies) kept falling. Nevertheless, if my analysis proves correct, we should be rewarded in due time.

A key lesson over the last few years is that conviction is essential in maintaining calm in times of turbulence. With growing assets, my focus has shifted from simply identifying statistically cheap stocks to dedicating more time to identifying companies and management teams with exceptional long-term potential I know well. As a result, iolite currently holds ownership stakes between 5 to 10% in a handful of its positions. Going forward, I intend to acquire even larger stakes to establish closer ties with management and exert more influence over company strategy and capital allocation. Ultimately, my aspiration is to attain a position where iolite has substantial control over the cash flow of the companies in which we invest.

Lessons from Charlie Munger

I recently revisited the journeys of renowned investors who went through periods of significant adversity, and Charlie Munger's remarkable story, as chronicled in Janet Lowe's "Damn Right!", stands out.

Charlie Munger initially practiced law as an attorney. His foray into equities began in the early 1960s after several successful real estate ventures. In 1962, at the age of 38, he founded an investment partnership alongside Jack Wheeler. This partnership achieved astonishing results in its first eight years. From 1962 to 1970, Munger's investment style and expertise generated an impressive annual return of 24.3%, a stark contrast to the Dow Jones Industrial Average's 6.4% gain during the same period.

Nonetheless, the years 1973 and 1974 proved to be a disastrous period for Munger and his partners. In 1973, Wheeler Munger declined 31.9% (while the Dow Jones Industrial Average fell 13.1%), followed by another 31.5% drop in 1974 (compared to the Dow's 23.1% decline). It's worth noting that this period was challenging for many investors. Berkshire Hathaway, controlled by Munger’s friend and increasingly close business partner, Warren Buffett, still mostly a textile operation at the time, saw its share price fall from USD 80 in December 1972 to USD 40 in December 1974. Gloom and doom permeated the news of Wall Street. Headlines proclaimed: "The Death of Equities."

By the end of 1974, the net asset value of the entire Wheeler Munger partnership had dwindled to USD 7 million, with 80% of the assets concentrated in just two companies it now controlled: Blue Chip Stamps and New America Fund. Limited partners who had invested in Wheeler Munger saw their accounts decline by over 50% from the peak reached two years prior. Munger stopped investing money for others and distributed the shares of his partnership's investment positions. He continued to manage the companies now under his control.

While losses in his personal investments never troubled Munger, he was deeply affected by the reported market losses in the Wheeler Munger limited partnership accounts: "We got drubbed by the 1973 to 1974 crash, not in terms of true underlying value, but by quoted market value, as our publicly traded securities had to be marked down to below half of what they were really worth."

In the following years, his cooperation with Warren Buffett deepened and the former Wheeler Munger investments were integrated into the growing Berkshire conglomerate. Munger became a director of Berkshire Hathaway in 1978.

How did his former clients do? The vast majority, 95% of the former Wheeler Munger Partnership investors, stayed the course and fared exceptionally well. Just one partner sold out in panic and lost about half of his investment. By the late 1980s, shares of New America Fund, which had traded at a low point of USD 3.75 in 1974, had appreciated to about USD 100 in cash and securities per share. Similarly, a share of Blue Chip Stamps, valued at USD 5.25 at the time, translated into 7.7% of one common share of Berkshire Hathaway. With Berkshire common stock reaching approximately USD 48,000 per share in March 2000, a former Blue Chip Stamps share was then worth USD 3,700, reflecting the partnership's enduring success.

Over the years, Munger became more relaxed about periods of declining stock prices. In 1999, when one of his investment entities, Wesco, saw its shares drop from a 52-week high of USD 353 to USD 253 due to rising interest rates, Munger remained composed: "I'm 76 years of age. I've been through a number of down periods. If you live a long time, you're going to be out of investment fashion some of the time."

Commodities - a historic opportunity

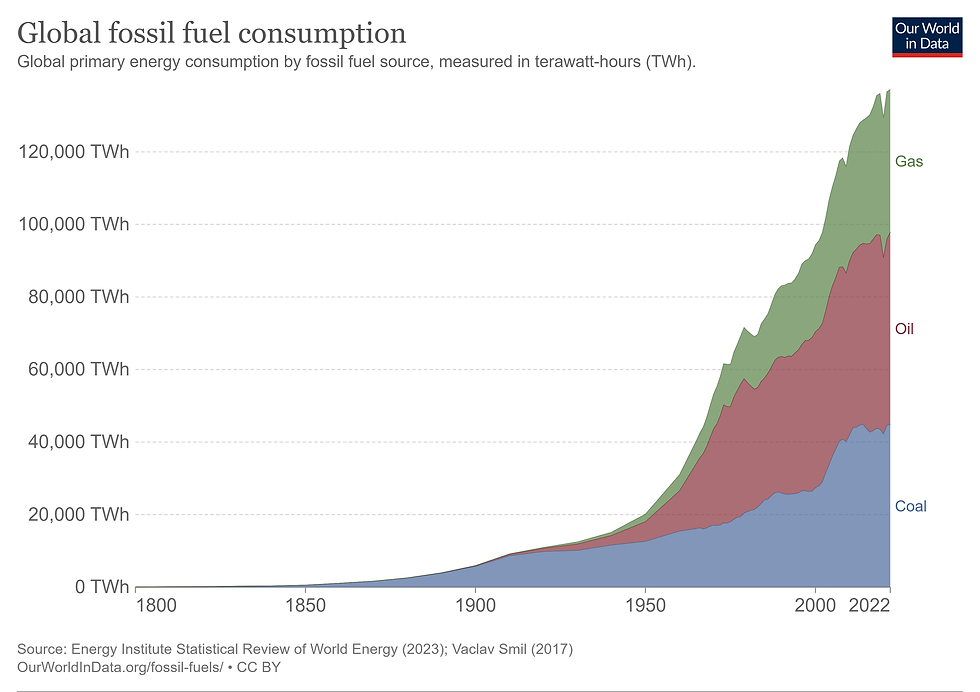

In my mind, investing in fossil-related commodities currently presents a unique and potentially unparalleled opportunity, as the prevailing market sentiment has led to widespread divestment of such assets and most market participants are categorically unwilling to commit capital to the sector.

While certain ESG considerations are undeniably critical for a sustainable future, the current hysteria is overshadowing the pragmatic reality that fossil fuels continue to be an integral part of our global energy mix, and their demand, especially in emerging economies, is growing faster than developed nations can reduce consumption. The sector has thus experienced sentiment-driven underinvestment, leading to reduced exploration and production activities, and in some cases, even premature asset abandonment. This, in turn, may lead to significant supply shortages and price spikes in the future.

Aside from ESG considerations, investors have also increasingly been shunning commodity-related investments due to the price volatility associated with traded commodity securities. The interconnectedness of global markets, geopolitical events, supply and demand imbalances, and currency fluctuations can be unsettling for investors who prefer more stable and predictable returns. Commodities are now historically underweighted in major indices, despite their significant strategic and economic importance. The sector thus offers an attractive technical opportunity for those willing to seek value beyond the mainstream and those willing and able to navigate price fluctuations and capitalize on undervalued assets.

Lastly, I believe the way the market is valuing commodity-related businesses is deeply flawed. Most market participants price such companies based on Net Present Value (NPV) calculations. NPV is a discounted cash flow (DCF) valuation method that estimates the present value of a company's future cash flows. Any calculated NPV heavily depends on assumptions about future commodity prices, the timing of capital expenditure, and ignores occasional windfall earnings.

Using iolite’s investment International Petroleum (IPCO) as an example, I will demonstrate how a traditional NPV calculation tends to vastly undervalue the company.

IPCO is an oil upstream business 50% owned and controlled by the Lundin family, known to be a best-in-class operator and capital allocator. It has two sets of assets:

a) Legacy assets in Canada, France and Malaysia that have a combined life of 16 years and produce around 50,000 barrels a day at lifting cost of around USD 20 per barrel (USD 30 all-in) at minimal capital expenditure requirements, and

b) A major Canadian oil field in development, Blackrod, with a life of about 80 years and expected to produce around 80,000 barrels of oil at lifting costs of USD 20 per barrel (USD 30 all-in) after an initial upfront investment of USD 800 million, including contingencies. Blackrod will almost be fully funded by cash on hand given record profits in 2022.

1. Common valuation approach: Most market participants use an NPV calculation, considering cash flows from now till year 80. This approach places significant weight on the initial Blackrod capital outlay in the early years and heavily discounts the positive cash flows upon project completion. Currently, the Enterprise Value is approximately USD 1 billion, closely aligning with my NPV calculation using a 10% discount rate and annual free cash flows from producing assets of USD 250 (corresponding to an average Brent price of USD 85).

2. Post the initial capex phase: Interestingly, if we run the same NPV calculation post the initial capital expenditure phase, the NPV soars from USD 1 billion to USD 2.5 billion. While this might seem counterintuitive, it aligns with the current market sentiment, reflected in trading multiples of more established Canadian peers like MEG Energy. Paradoxically, the market appears to discount the company's valuation for investment into future growth and expansion of the tangible asset base. This contrasts with the ongoing technology hype, where substantial capital expenditure into often unproven business models commands a premium and is viewed positively.

3. The value of optionality: Commodity producers are inherently sensitive to price fluctuations. A year or two of windfall earnings can significantly enhance investment outcomes. By investing in long-life, low-cost producers, one can increase the likelihood of realizing windfall earnings over the asset base's lifetime. Moreover, expanding the asset base with higher future production increases the potential size of any earnings windfall. Frequently, companies tread water for a few years, and then a single good year can offset the construction cost of an asset. Unfortunately, as most market participants base NPV calculations on static price decks, they often overlook such optionality and windfall earnings.

4. Inflation pass-through: NPV discounts cash flows, but commodities generally compensate producers for inflation over time. When consumers tighten their belts, they might cut discretionary spending, but they can't afford to skip paying essential bills like electricity. Therefore, it could make sense to examine nominal earnings over time. For IPCO, assuming steady production and a modest price inflation rate of just 3%, the lifetime nominal earnings could reach as high as USD 80 billion.

As demonstrated, taking a rational and mathematical approach while selecting the right assets can lead to fantastic opportunities, especially for those willing to ride the industry's cycles. Once again, we find inspiration in the wisdom of Charlie Munger, whose father made a highly successful oil royalty investment:

Berkshire AGM 2022

Warren: “Charlie, when did you buy that oil royalty in Bakersfield?“

Charlie: “My dad bought USD 1,000 or USD 1,500 worth of royalties before he died in 1964. And that goddam royalty is still paying me USD 70,000 a year.”

Comments